Evil May Day Causes

By 1517, the numbers of foreigners in London had increased as foreign trade had grown. Although they only made up 2% of London’s population, it was claimed that they often bought all the food in the markets leaving the English hungry and that foreign craftsmen were taking jobs and income from Englishmen.

In reality, England was facing an economic downturn following a poor harvest and difficult Winter. Much of the hatred stemmed from a conflict of culture: the French were considered arrogant and haughty by the English, while the French felt the English had no manners.

A London dealer named John Lincoln, believed that it was the presence of foreigners in London that was causing hardship for English traders. He approached King Henry’s Chaplain, Dr Henry Standish, and asked him to speak against the presence of so many foreigners in London during his Easter speech. When Standish refused he asked Dr Beal, the Vicar of St Mary’s in Spitafields, and he agreed to preach the sermon.

Around the middle of April Dr Beal addressed a large gathering and denounced all aliens who stole Englishmen’s livelihoods and seduced their women. He stated his belief that men should be allowed to fight the foreigners to save their country.

On 29th April the Venetian ambassador, Giustinian, sought an audience with the King. He told Henry that he had heard rumour that the people of London were to rise against foreigners on May Day. He voiced concern for his fellow countrymen in London. Henry reassured Giustinian that his compatriots would be protected. The Lord Mayor and officers of the city were told to enforce a curfew on the eve of May Day.

The following day the Mayor of London called a meeting of the aldermen of London. They met at Guildhall and discussed the steps that should be taken to prevent trouble arising on May Day.

The Events of Evil May Day

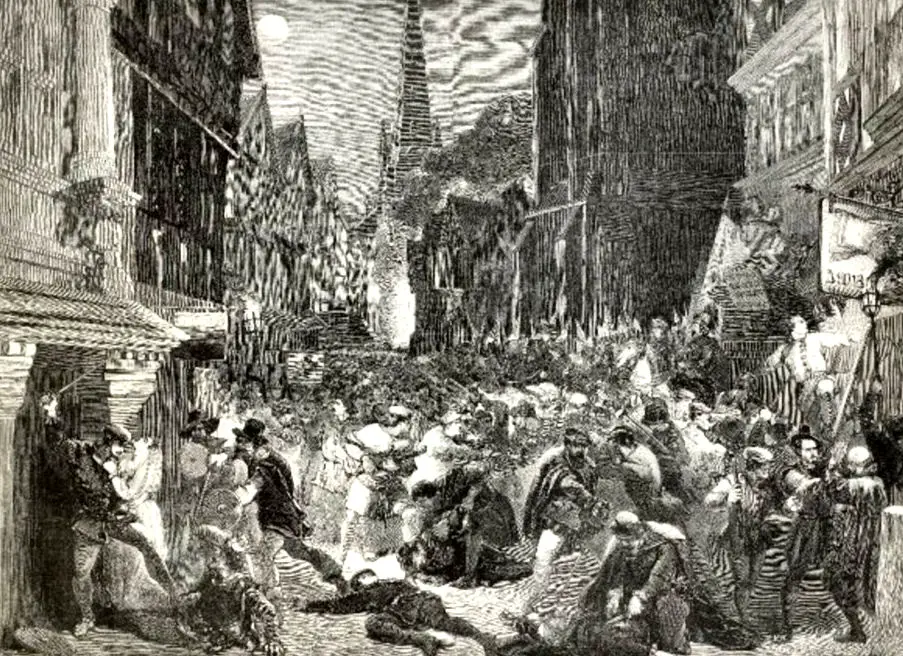

Trouble began on the eve of the festival when some young men broke the curfew imposed by the King. John Mundy, a local alderman, attempted to arrest one of the men in Cheapside and trouble broke out. It escalated and soon there were thousands on the streets of London. Most of their anger was directed at foreigners living in London. When they reached St Martin le Grand, an area inhabited by many foreigners, they were met by Thomas More, the Under-Sheriff of London. He was beginning to have some success at persuading the rioters to go home, when some of the inhabitants of the area began throwing stones and boiling water out of their windows and onto the mob below. This inflamed the rioters who targeted their homes and many were burnt to the ground.

The rioting quickly spread and in the early hours of the morning, news of the rioting reached the King. Henry ordered his own guard onto the streets and also sent word to the Duke of Norfolk to raise an army and march on London.

By around 3 am the rioting had calmed and the arrival of Norfolk’s 2000 strong army, commanded by the Earls of Surrey and Shrewsbury, restored peace to the city.

The Trial of the Rioters

On 5th May 279 rioters, including priests, apprentices and youths, were brought before the King at Westminster Hall. They were charged with treason on the grounds that to make an attack on foreigners while England was at peace with all countries was tantamount to treason. The hall was guarded by over 1,000 soldiers to prevent further trouble from the large crowd that had gathered outside.

Catherine of Aragon appealed to her husband to show mercy and spare the lives of the rioters for the sake of their women and children. Henry agreed and they were pardoned and released.

The following day John Lincoln and others identified as leaders of the riot were tried. Lincoln and 12 others were found guilty of treason and sentenced to be executed the following day.